State machines: How to stop making Horcruxes in your code

There are several ways of mitigating horcruxes. But visualisations can prevent bugs, so why not go further?

My code contains Horcruxes. I’m not proud to admit it, since to make a Horcrux you need to commit a murder. The murders seemed intuitive at the time, and were usually for expedience. But nonetheless, I am a murderer.

Let’s talk about how I got here.

The Soul of your app’s logic

For an app to remain maintainable, its soul must remain intact. For many apps, logic is usually expressed in changes to state and behaviour.

For instance, some logic for a modal might be expressed like this:

const modalReducer = (state = { isOpen: false }, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case 'CLOSE':

return {

isOpen: false,

};

case 'OPEN':

return {

isOpen: true,

};

default:

return state;

}

};This is the reducer pattern, popularised by libraries like Redux. In React, we'd use this reducer in a useReducer hook:

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(modalReducer);

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: 'OPEN' })}>Open Modal</button>;If you want to know what happens when you dispatch the OPEN action, you only need look in one place: the modalReducer. This part of your app is easy to keep bug-free, because all the logic for how it works is contained in one place.

But let’s say that requirements change. Now, before you open the modal you’ll need to fetch something from the API to check if you can open it. This seems intuitive enough:

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(modalReducer);

<button onClick={async () => {

const canOpenTheModal = await checkIfUserCanOpenIt();

if (canOpenTheModal) {

dispatch({ type: 'OPEN' });

}

}>

Open Modal

</button>The onClick handler is now making the API check to see if it should open the modal. If there’s a bug with the way the modal opens, there are now two places you need to check, the reducer and the event handler.

The soul of your business logic has been split. Just like that, you made a Horcrux.

Going beyond usual evil

The first Horcrux is never really the issue. You can survive one or two splits in your business logic. The trouble comes when you reach six or seven, split out over several 800-line files. I have wept over classes with dozens of methods, sequences with dozens of asynchronous steps.

Logic split into more than one place cannot be visualised. If it can’t be visualised, it can’t be modified, deleted or extended safely.

Let me make this plain: Any code that cannot be concretely visualised will, at some point, result in a bug.

There are several ways of mitigating horcruxes. You can push to make your code more readable, writing clean event handlers which don’t contain any logic. You can try to colocate as much as your logic as possible, for instance using ducks patterns.

But now we know that visualisation can prevent bugs, why not go further?

Statecharts

I recently embarked on the most complex task I’d ever attempted as a developer - building a video chat app with multiple third-party integrations. Most of the business logic would take place on a single page - the chat portal. I needed to handle multiple user types, chat, notifications, input changes... And many more things.

I’d been using XState, and read that it could be used for visualising complex behaviours, such as Ryan Florence’s checkout:

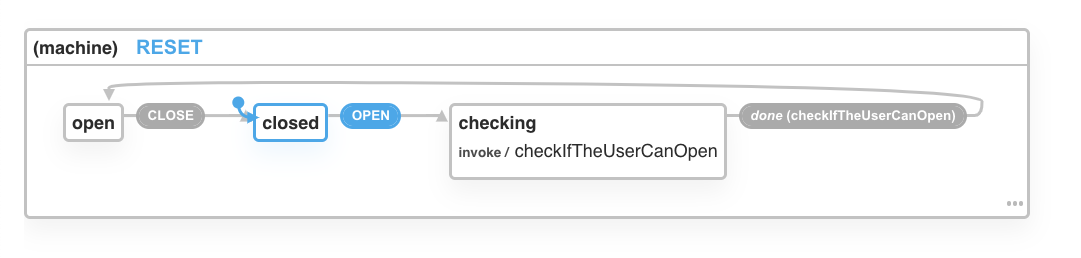

It produces clickable visualisations which you can share and walk through. For instance, the modal reducer above could be expressed in this statechart.

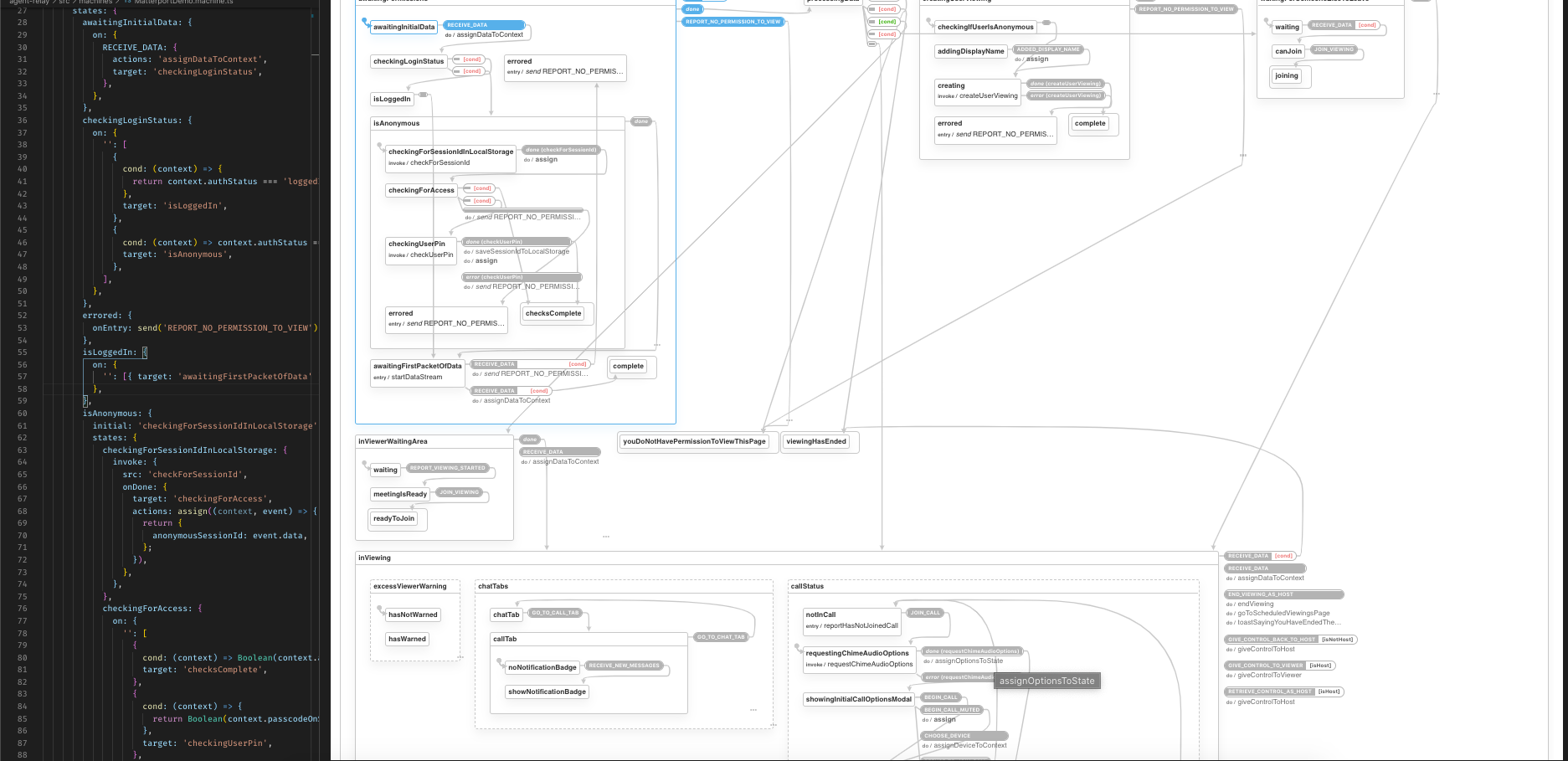

I knew that if I wasn’t careful, I’d end up with 25-30 horcruxes under my belt, logic carried in dozens of event handlers. So I wrote the machine in XState. I even wrote a VSCode extension so I could have the visualiser inline as I went along. Here’s what I ended up with:

Every part of this crazy complex app can now be visualised. I can see which conditions lead to which states. I can which actions are called on which events.

At an early stage of the process, I was even able to ask the client about complex interactions in the logic, just by walking them through the statechart. Weeks later, when it needed extending, I was able to insert a new piece of state without breaking anything else.

Any time someone needs to see how the viewing page works, they can fire up the visualiser. Their usual first reaction is one of terror. State machines don't create complexity, they reveal it. But by clicking through the machine, they can concretely see how the app works, and feel comfortable making changes.

Make a bet on XState

If you’re having trouble deciphering the logic of a legacy app, try visualising it in XState. Try working through a problem with a fellow dev. At Yozobi, we’re making a bet that state machines are going to change web development. If you want to learn more about them, follow me and we can try to heal our Horcruxes together.